Part 1: How to set strategic goals for an Innovation Barometer

|

Part 1 is designed to help: → Make the decision to create an Innovation Barometer → Motivate others to create one → Set strategic goals for your Innovation Barometer → Optimise its strategic use → Identify its target users → Define its use → Maximise its total value, including unforeseen uses → Form partnerships and reduce obstacles to promote its use → Show how other countries use their Innovation Barometers |

|

Table of contents: 1.1 Set your course of action and help others move in different directions 1.2 Look for partners and listen to sceptics |

1.1 Set your course of action and help others move in different directions

Because you're reading this document we assume that you are in a position to decide, or motivate others to decide, to establish an Innovation Barometer. We must warn you, however, that we do not provide definitive answers but rather questions to guide you in finding the right answers in pursuit of your own strategic goals. We do this by showing how others have set their strategic goals and by describing the purposes of previous Innovation Barometers.

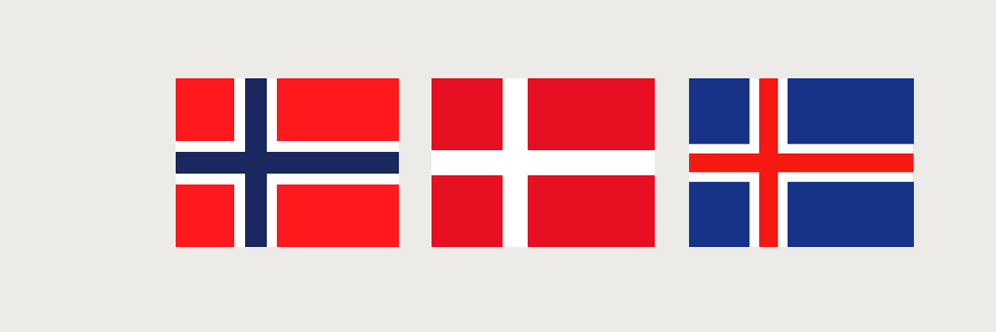

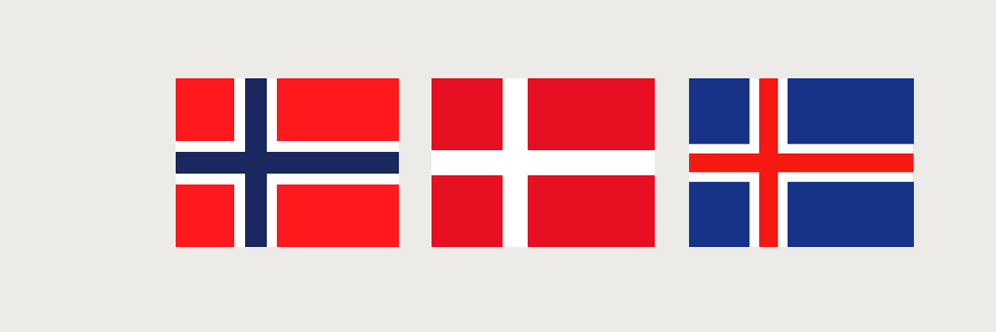

Based on experience in the Nordics, it is advisable to clarify the Innovation Barometer’s purposes in advance. Should it be used to devise national strategies? Or to help identify which innovation tools and approaches your public sector needs? Or something else entirely? Elucidating the purpose beforehand aids in selecting relevant topics, prioritising the questions and finding the right collaborators. A clear purpose also provides a better foundation when addressing opposition to the Innovation Barometer.

ACTIONABLE ADVICE 1.1:

DEFINE AND PRIORITIZE YOUR PURPOSES WITH YOUR INNOVATION BAROMETER

- Gather the main actors interested in having an Innovation Barometer.

- Identify its many purposes:

- What drives the various actors toward the Innovation Barometer? Which purposes can be defined within the group of interested actors?

- Explore connections and hierarchies between the purposes.

- Prioritise the purposes – what is the main purpose? What sub-purposes have a secondary or tertiary priority?

Process tip: Have a Post-it-Note party. Write one purpose on each Post-It Note to unmask the wide range of varied purposes that the actors bring to the table. Move the notes around to group them to identify patterns, connections and hierarchies. Discuss and decide on how to prioritise each purpose. If needed, use dot-voting to highlight the main priorities, which can lead to a discussion on whether they are the right ones to prioritize.

"We did the first Innovation Barometer to inspire public sector workplaces to innovate by showing what others are doing. But the goal was at bit too vague. To inspire others, barometer findings had to be transformed into self-assess- ment tools and handbooks, which is what we did. On the positive side, the barometer once and for all busted the myth about the public sector being unable to innovate, which was unexpected but very important."

Ole Bech Lykkebo, Head of Analysis

The National Centre for Public Sector Innovation (COI), Denmark

An Innovation Barometer is a powerful tool, but it does not tell you everything about public innovation. Once you have defined and prioritised the purposes of collecting data on public sector innovation, ask yourself this question: Is an Innovation Barometer the most relevant tool to serve your purposes? In any case, you should also consider alternative or supplementary methods of data collection.

For example, if an in-depth assessment of the outcome of a particular innovation or a deep understanding of particular types of complex innovation processes is required, a barometer will not be sufficient. If your purpose is to study the organisational culture's significance for innovation capacity, a barometer may be relevant as it enables comparisons across multiple workplaces. However, asking for only one answer per workplace will typically only give you the perspective of the manager or a trusted employee. If you want deeper insight into the organisational culture, you probably need to survey more employees and managers in each organisation, or use qualitative interviews or field studies. In short, let your purpose guide your choice of data collection methods.

ACTIONABLE ADVICE 1.2

ASSESS WHETHER AN INNOVATION BAROMETER IS THE RIGHT TOOL

|

Your data needs |

Innovation Barometer |

Alternatives |

|

Generalisable knowledge on public sector innovation representative of a large number of workplaces |

+ |

- |

|

In-depth assessment of the outcome of a particular innovation |

- |

Evaluation |

|

Innovation processes |

+ |

Qualitative interviews or field studies |

|

Organisational culture |

+ |

Qualitative interviews or field studies |

|

Your next data need... |

|

|

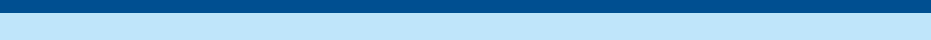

There are many examples of unintended uses of Innovation Barometer data being applied in unanticipated ways. The prerequisite is of course that data is made available for others to use. The recommendation is to clarify at an early stage whether data is to be shared – and with whom and how. Will the data be my data or our data?

ACTIONABLE ADVICE 1.3

DECIDE EARLY ON TO MAKE DATA OPENLY ACCESSIBLE

Decide early on where and how you would like to position your Innovation Barometer on the Data Openness Continuum shown below. Choose a position as far right as possible to maximise the combined value of your Innovation Barometer, including unforeseen uses.

There may be good reasons not to share all data with everyone, for example, if respondents are granted anonymity, but remember that anonymity can be maintained even when third parties are allowed to analyse data. Thus, our general recommendation is to keep data and results as accessible as possible. It is imperative, however, that systems are in place so respondents cannot be identified, not even indirectly.

There are multiple ways to make data available to others. To allow the correct interpretation of data, the methodology of data collection also needs to be available, just as any methodological issues should be highlighted.

USE CASE

OPEN DATA ACCESS

The Norwegian Digitalisation Agency, Digidir, has published anonymised Norwegian Innovation Barometer microdata at state level. This allows anyone to download the data and carry out their own analyses. Anonymising the data is challenging. Simply removing identifying variables (such as names) is often insufficient as individual workplaces can also be identified by combining multiple variables. Size, location and service area, for instance, can result in singling out an individual workplace.

USE CASE

RESEARCH DATA ACCESS

In Denmark specific projects approved by Statistics Denmark can gain access via its Research Services to Innovation Barometer microdata upon request. This makes it possible to enrich the microdata with existing registry data on individual workplaces and includes access to identifying information too sensitive to openly share. Unfortunately, these services are only available to international researchers affiliated with authorised Danish research environments, which means the data are not publicly available.

Since this is the case, the National Centre for Public Sector Innovation (COI) can, at its discretion, conduct analyses on behalf of other actors, such as news media.

USE CASE

ACCESS TO RESULTS

The Icelandic Innovation Barometer has an interactive interface that allows anyone to explore publicly available data and combine multiple variables without accessing microdata. The availability of a larger amount of raw data provides greater flexibility than fixed tables and figures.

Nonetheless, tables and graphics are also good ways to make data available as they are accessible and easy to reuse. We will have more to say about these possibilities in Part 2. How to communicate an Innovation Barometer.

1.2 Look for partners and listen to sceptics

An Innovation Barometer generates statistical knowledge on public sector innovation, which in most countries provides a whole new type of public sector innovation knowledge. Keeping Sir Francis Bacon’s famous aphorism "knowledge is power" in mind, these new types of knowledge can be expected to raise both expectations and concerns.

Our general advice is to ask yourself this question: Who in my country is likely to oppose the survey or its results? Engage in a dialogue with them to reach a compromise or an understanding.

USE CASE

ENGAGING IN DIALOGUE

The introduction of the first Innovation Barometer in Denmark in 2014 illustrates how concerns around the Barometer were treated. There was intense public debate in Denmark in 2014 that the public sector had become a new public management monster, with excessive requirements for measurements and documentation. Some argued that employees were forced to waste their working hours filling out forms that no one read instead of providing actual services to citizens. The view was that quality, efficiency and job satisfaction had all fallen victim to this rigid regime.

To suggest yet another measurement of the public sector in such a climate, of course, was bound to attract criticism. Sceptics predicted such a statistic was destined to become yet another benchmarking exercise that would shame, not help, municipalities, service areas, or professions that fell below average. COI and Statistics Denmark conducted seven open workshops to engage in an open dialogue with sceptics and participants from various organisations who were interested in completing the Innovation Barometer survey and using the results. This dialogue helped to sharpen the purpose of the survey, to reassure the sceptics and to engage more proponents.

One result from the workshops was a decision to refrain from the usual practice of Statistics Denmark to make the survey mandatory and instead to make it voluntary.

It was clearly communicated that the survey’s main purpose was to enhance public sector innovation by providing public sector workplaces with inspiration on how others had used public sector innovation to improve their services. In addition, it was plainly communicated that benchmarking was not the purpose of the statistic. The dialogue also resulted in adjustments in the questionnaire to simplify theoretical concepts and add new aspects, such as organisational culture. We will have more to say on the questionnaire in Part 5.

ACTIONABLE ADVICE 1.4

ADDRESS POSSIBLE CONCERNS EARLY ON

- Ask yourself and someone outside your ogranisation who in your country might be concerned about how the results will be used.

- Announce preparations for your survey publicly and monitor less enthusiastic responses.

- Assume that sceptics have valid reasons and invite them to give advice on how to increase the response rate and get the most out of the Innovation Barometer.

An equally important question is: Who are the other actors in my country who might also be interested in statistical knowledge on public sector innovation? Reach out to these organisations as well at an early stage, preferably before collecting any data, to create interest and perhaps find collaborators. Consider formulating the very purpose of the study with these partners to create shared owner ship and stronger legitimacy. Also consider adding a very limited number of questions that are valuable to your partners. Part 5 contains more information on the questionnaire.

ACTIONABLE ADVICE 1.5

MAXIMISE THE USE OF DATA

Ask yourself and a trusted colleague: Who beside us can use Innovation Barometer data? Expand and adjust the checklist below. Invite some or all on your list to a workshop BEFORE data collection begins. What advice can these actors offer? What can make the Innovation Barometer useful to them?

- Top officials

- Public sector innovators

- Policymakers

- Managers of innovation support

- programmes

- Interest groups

- Researchers

- Teachers

- Private consultancies

… and more

WARNING!

Your constructive invitation may can generate far more questions than any volunteer respondent would bother to answer. Do not offer to expand or complicate the questionnaire. Always be your respondent's guardian. This may disappoint your guests. However, they would have been more disappointed not to have been consulted.

1.3 How to use an Innovation Barometer

OECD guidelines for measuring private sector innovation have been in use since publication of the first edition of the Oslo Manual in 1992. Since then several countries have regularly collected statistical data on private sector innovation.

The availability of detailed knowledge on private sector innovation compared with the lack of knowledge on public sector innovation has perpetuated the myth that innovation only occurs in the private sector. For at least a decade the question of how to measure public sector innovation has been the starting point for much debate and several attempts to capture the essence of public sector innovation through measurement. So far, no consensus has emerged.

The Innovation Barometer aims to correct the imbalance between knowledge on public and private sector innovation by providing an operational framework that is applicable in and adaptable to most public sector settings.

Innovation Barometer data provide a new starting point for public sector innovation. Instead of discussing whether or not innovation occurs in the public sector the Innovation Barometer provides a yardstick to measure it and a meaningful foundation for discussions on how to further public sector innovation.

The rest of Part 1 shows the many uses that this operational framework has provided for measuring public sector innovation to date. We begin with uses closely related to public sector innovation, debunking myths, identifying gaps in innovation capacity and furthering innovation in the public sector. We then expand to even wider societal uses – research, education and policymaking.

Actors from 20 countries have been involved in co-creating the Copenhagen Manual, leading to another broadening of the perspective – from national agendas to transnational comparisons and collaboration. During the process of drawing up the manual this shift in mindset has become clearer to everyone in the Copenhagen Manual community. Consequently, our final case in Part 1 is the forthcoming Dutch Innovation Barometer, which has transnational comparisons as one of its explicit purposes.

USE CASE

DEBUNKING PERCEIVED AND CREATING NEW WISDOMS

Prior to the publication of the Norwegian Innovation Barometer, some expected the findings to convey, that public sector innovation only occurred in the largest and most centrally located municipalities in Norway. However, the results demonstrated that innovation by no means are limited geographically, but occurs extensively throughout the country. Now that these facts are established, further development can take its starting point from there.

In practice the Innovation Barometer generates evidence supporting a positive narrative about the public sector as innovative, competent and adaptive – especially when the data is combined with case studies on innovations in the public sector.

This positive approach creates a contrast to the public sector commonly being described as an expense, a tax burden and a second-rate institution compared to the private business sector.

WARNING!

Use the Innovation Barometer data and examples to tell positive stories about public sector innovation, without overselling the latter. Acknowledge that there are hurdles to overcome and avoid undermining your credibility by ignoring problems.

The aim of documenting innovation activity in the public sector is not to make the public sector look good. It’s about providing a solid, encouraging foundation for asking new questions – whether or not the data initially looks encouraging. It can also be used to identify gaps and to come up with solutions on how to fix them.

USE CASE

RAISING AND ANSWERING NEW QUESTIONS

When using data to address questions, new ones often arise. Politicians at local and regional level can play a crucial part in innovation. When the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS) compared Norwegian and Danish Innovation Barometer findings they wondered why local politicians in Norway did not initiate or promote innovation as often as their Danish counterparts. The Association decided to dig deeper by developing a supplementary questionnaire solely for local and regional politicians. It turned out that they were true innovators, with 87% of city and regional councils initiating innovation in their last term and with 69% of mayors involved in innovation processes. These percentages are higher than in Denmark.

WARNING!

In general do not expect Innovation Barometer data to directly help public sector employees innovate more successfully. You must transform data into something more concrete that is designed and tested to be easily applicable in certain situations.

USE CASE

IDENTIFYING AND ATTEMPTING TO FIX A GAP IN INNOVATION CAPACITY

Danish Innovation Barometer data showed that the overall innovation rate was high but that less than half of the innovations were evaluated. Consequently COI decided to focus attention on how to enable more and better evaluations of public sector innovations. A guide to help the evaluation process was developed, which took the Innovation Barometer findings as a starting point. These results were supplemented by qualitative findings on the difficulties with, and the solutions for, evaluating innovation. This combined knowledge served as a platform for a co-creation process with public sector employees who had an interest in evaluating public sector innovation.

USE CASE:

IDENTIFYING FACTORS THAT ENABLE AN INNOVATIVE CULTURE

The NZ Innovation Barometer is designed to identify and measure the factors that influence an innovative environment. The long-term goal of the Innovation Barometer is to create an enabling innovative culture in the public sector, where public servants have the tools, knowledge and permission to innovate, to encourage more innovations in addition to the politically driven innovations. The NZ Innovation Barometer will provide senior leaders with interactive data highlighting their agency’s strengths and areas for improvement, as well as recommendations to improve innovative ability, with progress being tracked over time.

"Public sector innovation is acknowledged as being vital to drive better outcomes for citizens. However, you cannot manage what you are not measuring, and currently we do not provide public sector senior leaders with measurement data, trends, benchmarks or examples to show how to lift innovative ability. Public sector leaders who want to see their agency deliver better outcomes are saying they need data and insights to take practical action."

Sally Hett, GovTech Programme Manager & Innovation Specialist

Creative HQ, New Zealand

An Innovation Barometer can also serve to make an impact on strategic agendas at a national level, e.g. when governments or parliaments discuss reforms or societal challenges. If that is the ambition, it is advisable to integrate the innovation barometer into the process from the beginning as opposed to simply publishing numbers at some point.

USE CASE

NATIONAL STRATEGIC IMPACT

In 2018 the Norwegian government announced its intention to boost innovation in the public sector to meet its goal of having a sustainable, efficient and modern public sector highly trusted by the public. To that end, the government engaged in an open process to write a white paper on public sector innovation to present to the Norwegian parliament in 2020. The Norwegian Digitalisation Agency carried out the Norwegian Innovation Barometer at state level with the explicit purpose of creating a knowledge base for the white paper. In combination with an existing Innovation Barometer covering local and regional levels, this provided a complete picture of public sector innovation in Norway. offentliginnovasjon.no

Iceland recently adopted a national innovation strategy that was intended from the outset to cover all areas of society, though the initial focus was on the private sector. The Innovation Barometer, however, provided a variety of solid new data on public sector innovation, eventually broadening the strategic focus.

Denmark showed a high rate of innovation overall but the percentage of people who made an effort to disseminate innovations to other workplaces was lower than expected.

As a result the National Centre for Public Sector Innovation began focusing more heavily on this area. In addition toolkits, networks and internships were established to enhance the capacity of the public sector to spread innovation.

Other knowledge has also helped form the foundation of these efforts, but the Innovation Barometer has supported and legitimised the overall course of action.

An Innovation Barometer can also provide a better understanding of both public and private sectors innovation that furthers collaboration between the sectors. It enables comparison and can pave the way for learning, cooperation and partnerships between the public and private sectors, either in the form of knowledge and technology transfer or of service provision.

USE CASE

BETTER UNDERSTANDING AND MORE COLLABORATION

Statistics Sweden and the Swedish innovation agency Vinnova are preparing the second round of the Innovation Barometer. This will involve making more comparisons with the corresponding survey in the private sector to provide mutually beneficial learning.

Greece conducted a public sector innovation survey in 2020 that was inspired by the Innovation Barometer. One of the purposes was to pave the way for mutually beneficial collaboration and partnerships between the public and private sectors, either as knowledge and technology transfer or as service provision.

Good management thrives on good data. An Innovation Barometer can also provide data and knowledge that can be integrated into on-the-job training programmes for present and future public sector leaders.

USE CASES

EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT TRAINING PROGRAMMES

A survey of local Norwegian municipal politicians that was conducted after comparing the Danish and Norwegian Innovation Barometers showed that the politicians do not feel that they have sufficient knowledge to effortlessly initiate innovation processes. To meet this need the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS) is developing a course on innovation management for elected leaders.

The Danish edition of Canadian author and public servant Jocelyn Bourgon’s internation- al bestseller, A New Synthesis of Public Administration – Serving the 21st Century (2017) incorporates Danish Innovation Barometer data. Her Danish co-author, Kristian Dahl, uses the Innovation Barometer in his perspective on emergence, one of the four management perspectives the book covers. Bourgon’s work also provides a structural framework for the Danish Ministry of Finance's comprehensive management development programme at state level and for an ambitious KL (Local Government Denmark) executive development programme at local level.

Iceland's Innovation Barometer data have directly aided the Icelandic Ministry of Finance in improving education on innovation to chief executive officers in the public sector.

Innovation Barometer data have also been used in educational institutions and in research contexts.

USE CASE

INNOVATION BAROMETER DATA USED FOR RESEARCH AND EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES

Innovation Barometer data has been used for various research purposes, for example, in the peer-reviewed article "Public Value through Innovation: Danish Public Managers' Views on Barriers and Boosters" (2020), published by the International Journal of Public Administration and authored by Ditte Thøgersen, a PhD student at Copenhagen Business School, and co-authors Susanne Boch Waldorff and Tinne Steffensen.

Daði Már Steinsson’s University of Iceland master’s thesis, "Public sector innovation: How can the government promote further innovation in public sector workplaces?", is based on data from the Icelandic Innovation Barometer.

Researchers from the University of Aalborg in Denmark have been granted access to Innovation Barometer data at Statistics Denmark’s research access. The Norwegian Innovation Barometer has stimulated interest in doing more research on public sector innovation with or without use of Innovation Barometer data. The findings to date have inspired researchers at institutions of higher learning to ask new research questions.

COI’s handbook, NYT SAMMEN BEDRE [NEW TOGETHER BETTER], is used to teach public sector innovation in upper secondary and higher education, putting the Innovation Barometer on the syllabus in Denmark.

Instead of continuing to mainly rely on data on innovation and entrepreneurship from the private sector educational institutions in Norway are increasingly using Innovation Barometer data. This has lead the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities to conclude that student interest in working in and for the public sector is likely to increase when introduced to an innovative public sector through their education.

"We actively support the use of the Innovation Barometer at educational institutions and are pleased that several students are using our data in their master’s thesis. We believe it opens the eyes of young people to the fact that innovation also occurs in the public sector, encouraging more graduates to seek public employment."

Une Tangen, Senior Advisor

Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities, Research, Innovation and Digitalisation

Once results from Nordic Innovation Barometers were published actors with various interests have also utilised the data to formulate policy. Thus, Innovation Barometer data have been used to strengthen the underlying evidence-based foundation of existing discourse and new policies, which may lead to public sector innovation playing a role in societal contexts where it is generally not taken into consideration.

USE CASE

PUBLIC AFFAIRS

In 2017 the Danish government announced a reform to produce greater cohesion to achieve a more citizen-centred public sector. The aim was for municipal and regional authorities with overlapping responsibilities to provide seamlessly coordinated services. Although Local Government Denmark, an interest organisation comprising Denmark's 98 municipalities, agreed with the reform's overall purpose, it emphasised that shortcomings were not due to the inability of the municipalities to cooperate, highlighting innovation in its argumentation. Citing the Innovation Barometer, the organisation pointed out that 78% of municipal innovations occur in collaboration with one or more public or private actors outside the individual workplace.

A supplementary survey of local politicians completed in conjunction with the second round of the Norwegian Innovation Barometer showed that about half of all mayors found that certain legislation or other centrally established rules inhibited local innovation processes. The Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities has incorporated these findings in its argument for reducing central regulation. This view is not new, but now innovation data is embedded in the ongoing dialogue between local and regional authorities and the central government.

USE CASE:

ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING AND TRANSNATIONAL COMPARISONS

The forthcoming Dutch Innovation Barometer surveys central government, municipalities, provinces, water management agencies and public collaboration authorities. One of its aims is to offer top civil servants in these organisations the opportunity to participate in organisational learning by reflecting on the performance of their own organisation compared to others. This perspective will be strengthened by benchmarking Dutch results against some of the results of the Nordic countries. In addition, the Dutch Innovation Barometer will include a question on the impact of COVID-19 on the performance of the organisations.

USE CASE

USER-CENTRIC INNOVATION DATA FOR ORGANISATIONAL DECISION-MAKING

The experimental project InovX: Innovation Panel for Public Sector was designed to diagnose innovation strategies used in the Portuguese public administration. The Portuguese Experimentation Lab for Public Administration (LabX) started a collaborative team with scientists and experts, adopted an experimental approach and acquired a representative sample from 92 public organisations spread out across various administrative levels and areas of government. Innovation diagnoses were generated for each organisation based on the data collected and individually sent to their managers, providing relevant and usable information about their innovation strategies and capacities. An interactive dashboard prototype was also used to explore the provision of customised options visualising the information available to end users. This user-centric approach allows the detection of challenges in terms of existing capabilities and supports public organizations into making sustainable and impactful decisions.

USE CASE

DIFFERENTIATE INNOVATION SUPPORT TO MEET DIFFERENT NEEDS

The Greek Ministry of Interior serves as a horizontal unit for innovation throughout the public sector. In this capacity, it provides innovation support to enhance the skills of public servants and the innovation capacity of public organisations. In 2020 the Ministry did a survey on innovation capacity targeting all three levels of government: ministerial, regional and local. The purpose was to do data management to put public organisations into clusters, such as innovation lions, allowing the design of targeted support to better meet the various needs of the different clusters.

Download part 1

Download a full PDF-version of part 1: How to set strategic goals for an Innovation Barometer.

Download part 1 (PDF)

Comments

Paul Sauer (COI - Denmark)

26. januar 2021 - 11:14

Please write your own comment below.